The Eclectic World Of Hormazd Narielwalla

- 13 Nov '18

- 9:30 am by Payal Mohta

What happens when bespoke English tailoring patterns are resurrected in a contemporary collage? When freed from the functionality of fashion they find themselves exploring the lanes of multiculturalism, gender and nostalgia? And when isolated, they become enigmatic pieces of beauty?

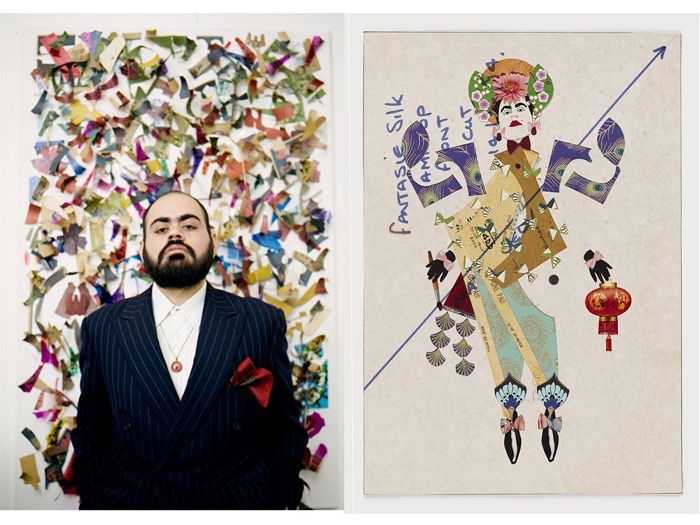

The answers to these questions lie with London-based Indian artist Hormazd Narielwalla and his eclectic creations.

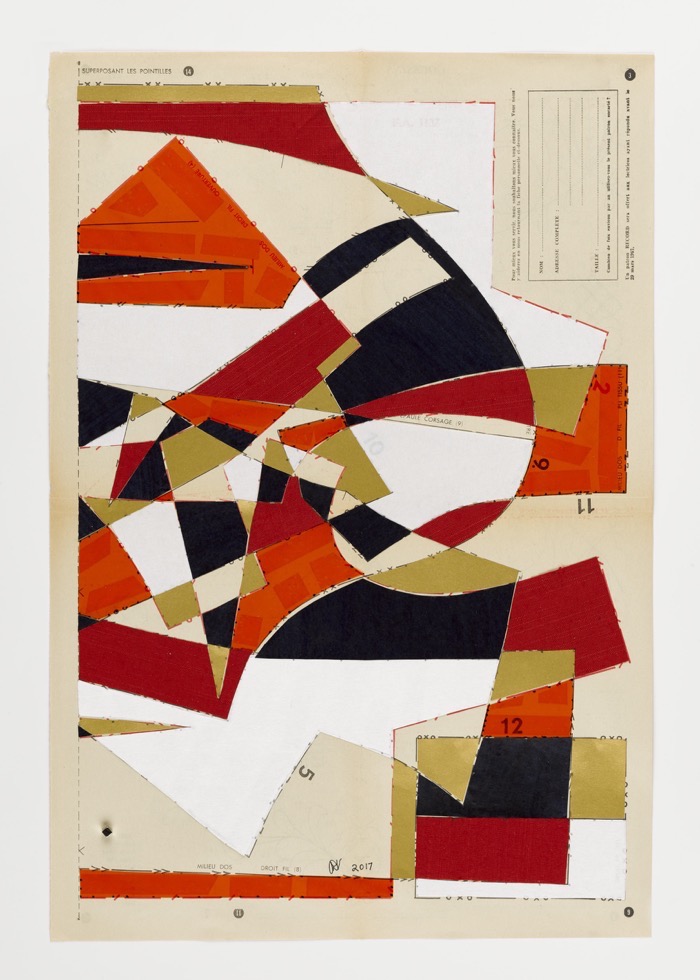

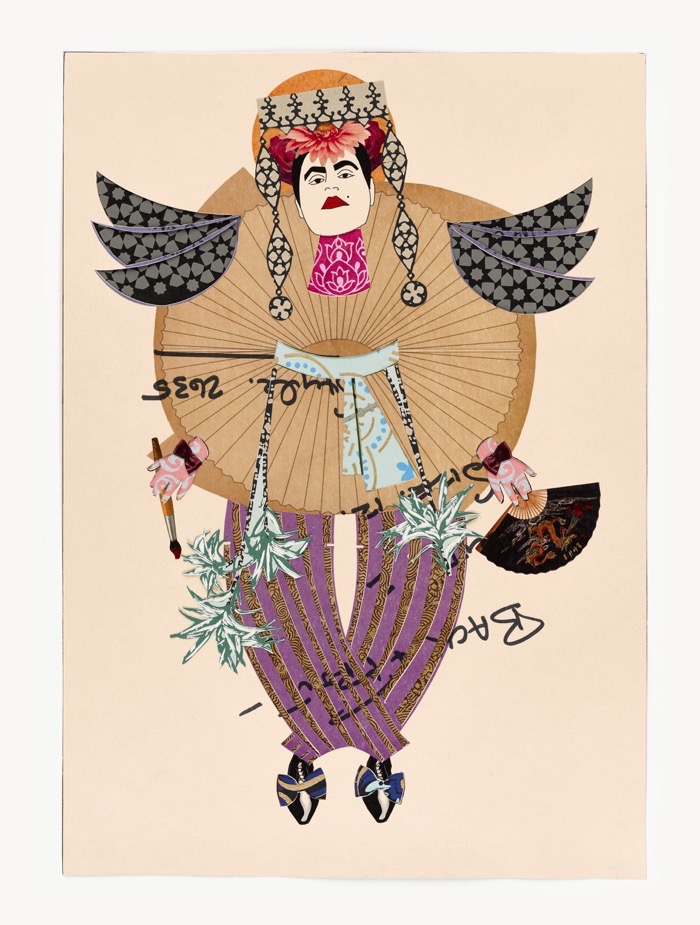

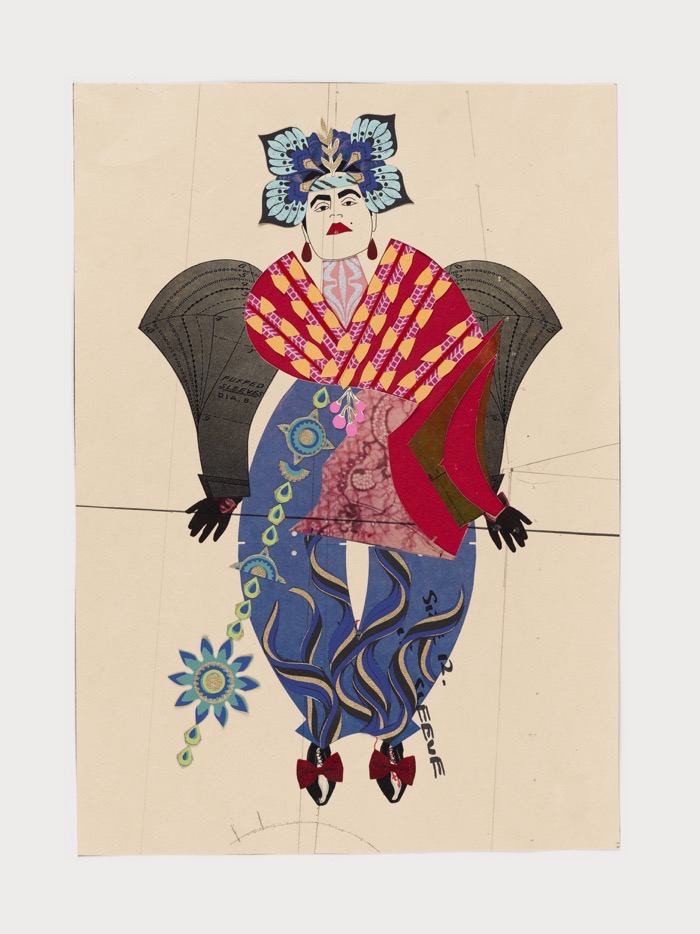

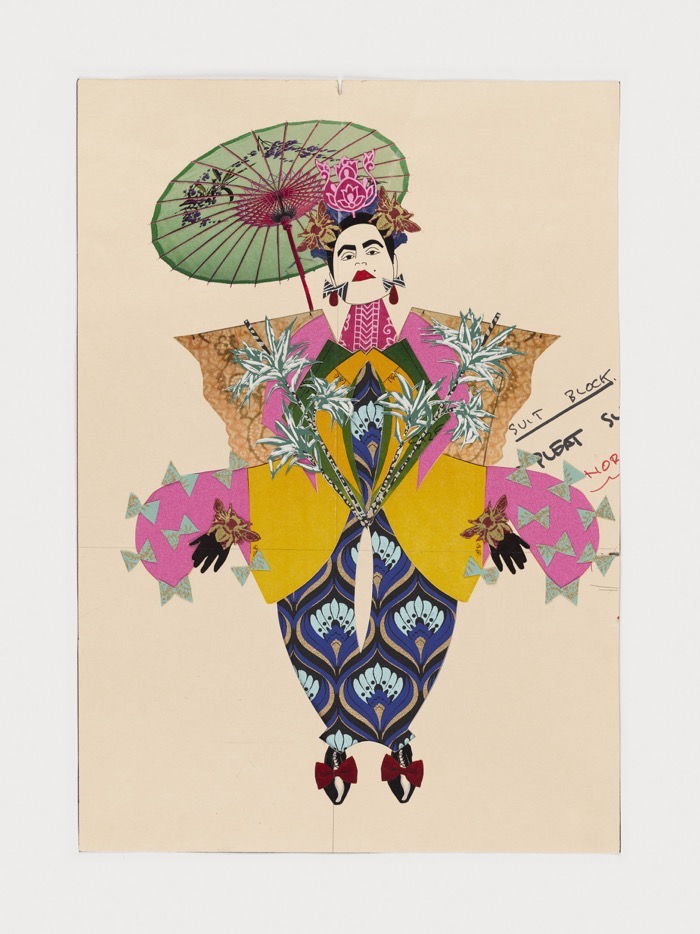

Narielwalla uses bespoke Savile Row tailoring patterns and their antiquarian and contemporary trade counterparts, to create artworks exploring the body in abstract form. From 1970s luxury lingerie, antique magazine inserts to uniforms from the British Raj are what form the guidebook to his art which explores the human body in its abstract form. While his muses, who range from the fiery Frida Kahlo to the nonchalant dandies of East London interweave both intimacy and inclusivity in his work.

A name found in prestigious galleries across the world —including London, Sweden, Tokyo and India, Narielwalla also finds his work being repeatedly commissioned by commercial clients.

So, Design Pataki decided to catch up with this groundbreaking and immensely talented artist. At the core of his work we found that though it stems from the deeply personal, it still exudes myriad universal connections for those who will allow themselves to delve into its visually consuming depths.

Design Pataki: Tailoring patterns and paper collages aren’t the conventional duos. Tell us about how you developed your signature style?

Hormazd Narielwalla: During one of my first ever conversations with William Skinner; Managing Director of Dege & Skinner — an English tailoring firm, he told me that when his customers passed away he would shred their patterns. They had no use for these parchments, as the ‘body’ no longer exists. This had a profound effect on me, and I convinced him to give them to me.

In my book Dead Man’s Patterns (2008), I talk about how these fragments of paper become a poignant memento of the knowledge one man once had of another’s body. The book charts the shifting relationship between the deceased man and his tailor, from maturity to senility – and also marks a wider change in the status of bespoke clothes as a craft form. After the success of the book, I started exclusively using patterns in my practice, which predominantly works in the medium of collage.

However, now it has also moved into 3D sculpture, original prints such as woodblock and lithography and a continual exploration of the book form.

DP: The muses of your work are diverse. Is there a unanimous quality that draws you to them?

HN: I’m drawn to characters that I can somehow find a connection with and relate to their persona. For instance with Frida Kahlo – I too had a back injury, not as horrific as hers, but nonetheless, I was stuck in a bed for months where I began to draw and started to build a fascination for fashion. The East London Dandies that I draw are humorous, detailed oriented who express originality. As a foreigner living in London, I find them exotic.

I like to escape into other people’s identities for a moment, and this is captured on paper, with bits of other papers and a sketch.

My next muse that I find very inspiring right now is Hamish Bowles.

DP: Your work explores identity through multiculturalism, gender, nostalgia and loss. How much of this inspired by your own personal experiences?

HN: I’m a Zoroastrian, Indian-born gay man living and practising art in London. I see myself as a citizen of the world, and a very happy product of globalization. Prior to moving to London, I lived in Wales for a few years and New Zealand where my family live. My personal diaspora is about the freedom of movement and the experience of culture on multiple levels. Take London – it’s a melting pot of many nationalities, where over 100 languages are spoken here. London is built on immigration.

So when Brexit was voted for, it burst the bubble that I live in. I responded to it by making a series of works — Lost Gardens, a beautiful metaphor to humanity. The garden is a place of solitude and thrives in cycles. It lives; it grows, it flowers and then dies, and comes alive the following year.

There was a sense of loss when the vote went to the left side. You might agree or disagree but the country decided to entangle 40 years of partnership which perhaps 40 years from now like the Lost Garden, might not leave any traces of that relationship.

DP: Inclusivity of class, culture, and gender is evident in your work. Has this been a conscious choice?

HN: My moral compass believes that people from all walks of life should have an equal opportunity in the making and consumption of culture.

When I was growing up in India, one of the things that upset me was the treatment of the trans community. Let’s not forget those royal courts before the British came in, where hijaras were seen as enlightened people of wisdom and grace, and even divinity with Ardhanarishvara — the merging of Shiva and his consort Paravati. The term literally translates as “The Lord whose half is woman.” I hope their status improves and they have a voice in mainstream thinking. So yes, inclusivity is definitely a conscious choice in my work.

DP: What are your thoughts on the present contemporary art scene in London?

HN: London is a powerhouse for the making of culture, consumed by an international audience. Since the financial crash in 2008, the Art world has suffered a few blows in cutbacks. I would like to see fewer cuts of Arts funding by the government and also to not cut the arts in education and learning. To also incorporate the arts in programmes for rehabilitation and mental health.

DP: Tell us about your book Paper Dolls and what readers can expect from it?

HN: Paper Dolls (2018) is a book about exploring my own personal identity and navigating in a global world. There’s a rise in nationalism and a reaction to globalization. Everyone hasn’t benefited from the world becoming a smaller place and I understand the impact it has had on sways of communities who have been left behind. This has led to the polarization of politics that makes our Prime Minister come out and utter the most irresponsible statements like, “If you are a citizen of the World, you are a citizen of nowhere!” sent shivers down my spine.

Mixed race children in the UK, are the fastest growing group. How would a child with a French mother, and a British father residing in the UK feel? The book is a reaction to the feeling that as an individual I can be whoever I choose to be and I should be celebrated for it. For example, in the book, I take on the persona of a woman I came across sitting in a Café —Japanese, striking, petit, feminine and beautiful. Nothing like me! Only to realise that there is no audience for my performance and instead of performing my new self I should just ‘play’ me.

Photographs courtesy Hormazd Narielwalla