Looking Back At The Legacy of Modernist Mohamed Melehi, As A Way Forward

- 2 Nov '20

- 9:30 am by Beverly Pereira

“The relevance of Mohamed Melehi’s artistic legacy goes back to his pioneering role in postcolonial and cosmopolitan art history. Rooted in the Independence of Morocco in 1956, his ability to navigate the shifting borders of the region allowed him to create a genuine visual culture for the development of the Global South. Anybody interested in rethinking those borders today can find true inspiration in him.”

– Morad Montazami, Curator, New Waves: Mohamed Melehi and the Casablanca Art SchoolArchives’

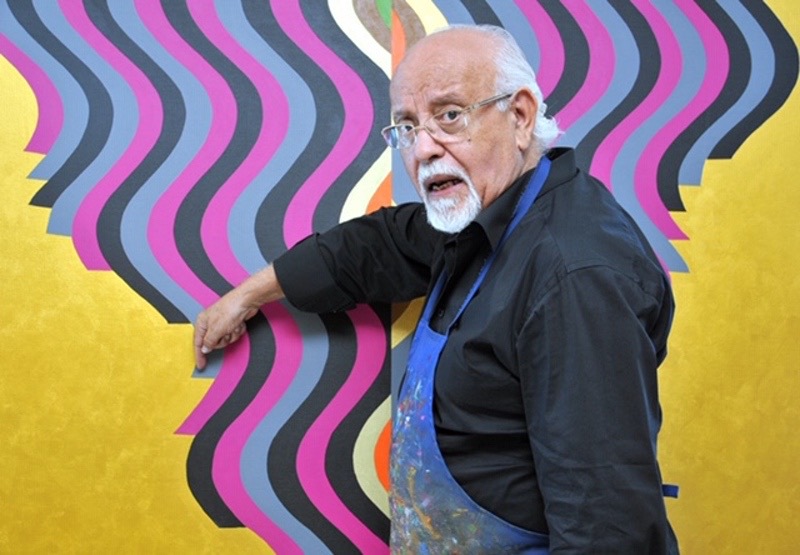

Photography Credit: H. Chergui, 2017

Activism and art are not strange bedfellows. Historically, the visual arts, music too, has been central to some of the most powerful social movements fuelled by political unrest. From the American Civil Rights movement and the Arab Spring, right up to the ongoing Black Lives Matter movement in America and the UK, there has been a song, a symbol and a chant to bind people and protest. Closer to home, an art show at AlserkalAvenue’s Concrete gallery in Dubai comes at a fitting time. The show which opened in September and will run until November 21, brings together the works of Moroccan artist Mohamed Melehi, one of the world’s foremost Modern artists whose transnational art forged a new identity in post-colonial Morocco.

Melehi sadly passed away on October 29, 2020, in the midst of this rare exhibition and at the very time of writing this feature. But the ongoing Dubai retrospective titled ‘New Waves: Mohamed Melehiand the Casablanca Art School Archives’ is proof of the magnitude of his work. The show was first exhibited at the Mosaic Rooms in London and then at the Museum of Contemporary African Art Al Maaden in Marrakesh last year. Curated by Morad Montazami who has spent years documenting the artist’s career, and presented by the Alserkal Arts Foundation, the Dubai Retrospective is extensive yet befittingly intimate as it traverses Melehi’s intercontinental journeys, inspirations and works chronologically. It is quite plainly a deep dive into the life of an artist who brought about not just an aesthetic revolution in post–war Morocco, but one that left an imprint on the very fabric of a country torn apart by authoritarianism and cultural unrest.

The Pre-Wave Years

Born in the seaside town of Asilah, Morocco, in 1936, Melehi was one of the earliest Moroccan students to have graduated from the National Institute of Fine Arts of Tétouan in 1956. He went on to pursue art, first at the Royal Academy of Arts in Seville and then in Rome before accepting a grant by the Rockefeller Foundation to study at Columbia University in New York in 1962. It was in New York that he met fellow luminaries in the arts — artist Frank Stella and musicians like Miles Davis, Charles Mingus and Thelonious Monk — that he developed a new visual language influenced by both Hard-edge painting and the unquenchable thirst for freedom in 1960’s America.

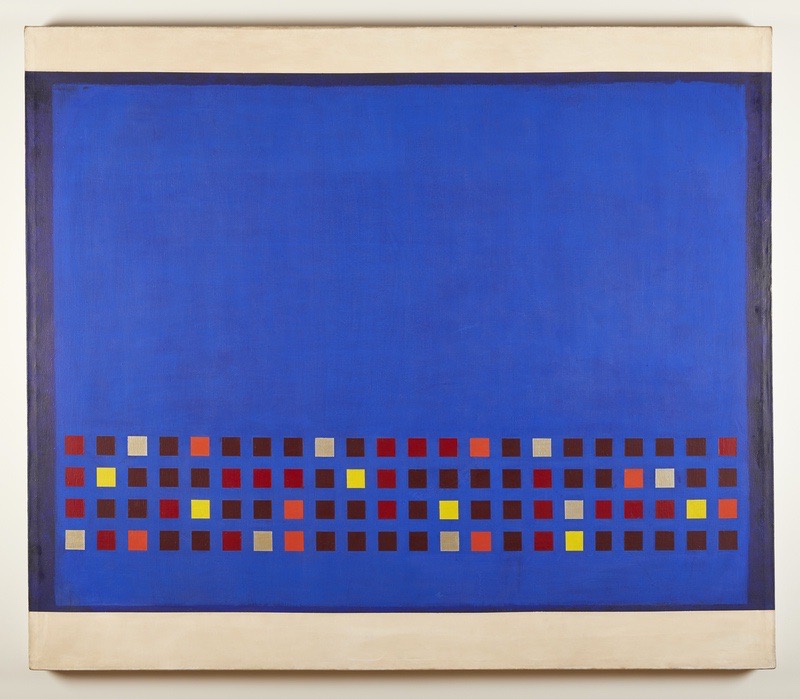

Where Melehi used sombre hues and horizontal and vertical lines in his abstract pieces in Rome, he was now incorporating curves in a varicoloured, mind-bending palette in New York. One encounters the spirit of this transformation at the outset of the exhibition itself, where his famous works exhibited at Rome’s Galleria Trastevere in 1957 are placed alongside his diptych ‘Solar Nostalgia’ from his 1963 group show at the MoMA titled ‘Hard Edge and Geometric Painting and Sculpture’. Only a year before, he had painted ‘Sleeping Manhattan’, a very iconic piece inspired by the city’s skyscrapers. The colourful, soft curves he was now using preceded what would soon become his most emblematic motif – the undulating wave, which remained key to his repertoire till the very end.

The Homecoming

The terms of his scholarship stated that every international student must return to their home country upon completion of the American-funded scholarship, which was at the time designed “to unite, to maintain and enlarge the friendly solidarity which united or should unite civilised beings”. And so, Melehi returned to Casablanca in 1964, arriving in a country eight years after it had gained independence from the French protectorate and that was now in the throes of political unrest and public protests against the tyrannical rule of King Hassan II.

A Bow To The Bauhaus

Art was Melehi’s response to the resistance in an impactful yet peaceful manner. Once again, we see the development of a new aesthetic when he took up a post at the École des Beaux Arts in Casablanca where he taught photography from 1964 to 1969 and, along with fellow artists Farid Belkahia and Mohammed Chabaa, urged students to look to local art and craft traditions for inspiration on field trips to the hinterland. He had just returned from the West with a desire to bring to his canvas neither still-life drawings nor figurative art; Melehi, of Berber and Arab ancestry himself, was drawn to the rich legacy of Afro-Berber art. Melehi, Belkahia and Chabaa, having well assimilated their respective artistic styles in America and Europe, formed a collective for ethnographic research and artistic experimentation. Locally woven rugs and intricately crafted silver jewellery soon replaced plaster casts in the classrooms. The New Waves retrospective brims with archival material that supplements Melehi’sworks. We see the integration of new methodologies at the Casablanca arts school in a section titled Reframing the Wave: Between Afro-Berberism and Postcolonial Architecture, which introduces the viewer to the very objects that once inspired the artist and his students — carved wooden doorposts, Berber jewels, carpets and wicker baskets — and a host of previously unseen paintings from private collectors.

During these years, Melehi found his own visual language in the fusion of the region’s Islamic art and symbols and the architectural style of Bauhaus. His penchant for geometry and solid colours stuck on, but he was now employing a modernist expression through calligraphy and graphic depictions of rays, flames and the iconic wave into his work. In 1966 Melehi designed the covers of leftist national magazines, like Souffles, in which socio-political commentary played a key role in the protests at the time. He also started working with wood and collaborated with several architects in the region to paint frescoes and ceilings of hotels and buildings.

Democratising Art

Throughout the exhibition, one gains an insight into the magnitude of Melehi’s career not only as a painter, muralist, photographer, graphic designer, interior designer and teacher but also as a cultural activist who took his art to the people. The Casablanca School as a Modern art movement and school of thought remains highly regarded in that it democratised art and played an incomparable role in the resistance. The loosely named renegade school of visual thinkers also laid the foundation of Morocco’s contemporary art scene which continues to be employed as a means of activism.

Photography Credit: Mustafa Aboubacker for Seeing Things, courtesy Alserkal

Integrating the Bauhaus approach of employing art for the good of the public as opposed to merely approaching it as a luxury, Melehi and his fellow artists staged a radical exhibition on the streets of Marrakesh’s Jemaa el-Fna Square in 1969 to oppose the state-run Salon de Printemps and to communicate the idea of art as a means of expression and freedom. The radical street exhibition titled Presence Plastique is well-documented as a series of photographs at the New Waves retrospective. He also started to use car paint in his cellulose paintings in a bid to use materials unremoved from the common man’s world. In 1978, Melehi founded the Asilah MoussemFestival of the Arts which showcased the works of young artists and which continues to be held every year.

Photography credit: Seeing Things courtesy Alserkal Avenue

Painted on a wall just outside the gallery at AlserkalAvenue, a mural, larger than life, comprises bright graphics waves — Melehi’s signature motif. The Melehi-inspired mural is more than just a nod to his significant contributions to visual history and cultural activism in his home country of Morocco and beyond. Its presence instantly sets the tone upon entry and exit of the show as if to remind the visitor of Melehi’s philosophy which leaned towards creating an aesthetic unbound by stodgy institutions or art trapped within the stark walls of a gallery. At a time when almost every country of the world is rife with greed, corruption and disregard for its people, to look back at Melehi’s life and work is to understand just how powerful the intersection of art and activism can truly be.