Making Space For Cultural Identity: A Conversation With Sound Artist Lakshmi Ramgopal

As a way of maintaining ties to her Indian cultural heritage, Lakshmi Ramgopal started learning Carnatic music and the classical dance form Bharatanatyam when she was in elementary school. This wasn’t easy considering her home was one of many in suburban Boston which was predominantly white and so she often found herself at cultural crossroads. In addition to being a sound artist under the moniker of Lykanthea, Ramgopal is also a historian of the Roman Empire and currently teaches as Assistant Professor at Columbia University. She was most recently awarded the Edgar Miller Creative Spirit Award. She has shown her work at The Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive in Los Angeles, Lincoln Park Conservatory in Chicago and has an upcoming show at Krannert Art Museum in Champaign, Illinois.

Aware of how deeply nuanced and complex, identifying as a South Asian in the United States and in the Indian subcontinent can be, she says “one of the tricky things about being from South Asia is how many different groups you can identify with are based on ethnicity, linguistic practice, religion and unfortunately caste.” It wasn’t until college that she was able to verbally articulate the feeling of being from many places at once. “You know there was that typical tension I think growing up that most children of immigrants feel wherever they are located. I really resented feeling so different where I grew up,” she reflects on her experience growing up in the 90s and how inclusive identity discourse has gotten since then, “now there is a lot of pride about being different. Those were different times.” Ramgopal’s trajectory is proof that making space for different cultural identities can be conducive to creativity. In this interview, Design Pataki talks to Ramgopal about her upbringing, her multiple cultural identities and how a dual career in the classics–both in music as well as history– has informed her art-making.

Design Pataki: When and how did your journey with music and art-making begin?

Lakshmi Ramgopal: I was born in Boston, MA and my parents are both immigrants from India to the US. They came in the big wave of immigrants from South Asia in the 70s. As a way of maintaining my ties to cultural heritage, my mom, who is a vocalist, insisted I learn Carnatic vocals and Bharatanatyam when I was six or seven years old. I also learned the western flute and violin. These were a huge part of building my relationship with my homeland but also things that middle-class American kids did to include on their college applications. I didn’t have a lot of emotional attachments to any of it. Although I did really love dance, I even did the arangetram (i.e. made my on-stage debut after training).

In my first few years of graduate school, I was in different kinds of bands like the third wave, and fourth wave guitar electro-pop bands and that was really exciting for me. It was the first time I started creating music instead of performing music that someone else had composed. I hated Carnatic voice lessons for many reasons, especially because I just don’t think I have that Carnatic M.S. Subbulakshmi kind of voice. Till date, I continue to really struggle with singing. I always found that stressful because there are lots of women–like my mom, my grandma and even my sister-in-law– in my family are gifted with amazing voices.

Eventually, I kind of leaned into it and started writing my own music that strongly reflected me. It was in that process of transitioning to electronic music that I learnt how Carnatic music had fundamentally altered my experience. Whereas with dance it wasn’t until 2017 when my maternal grandmother passed away that I really shifted gears and started to incorporate movement into my work. I started to regain interest and find ways to bring dance into my projects. I think it came from a need to physically engage with the projects I was doing as a way to process my grief.

Design Pataki: Could you take us through your projects- Maalai in 2017 which deals with intergenerational histories, and A Half-Light Chorus in 2018 which is a more nostalgic and playful piece?

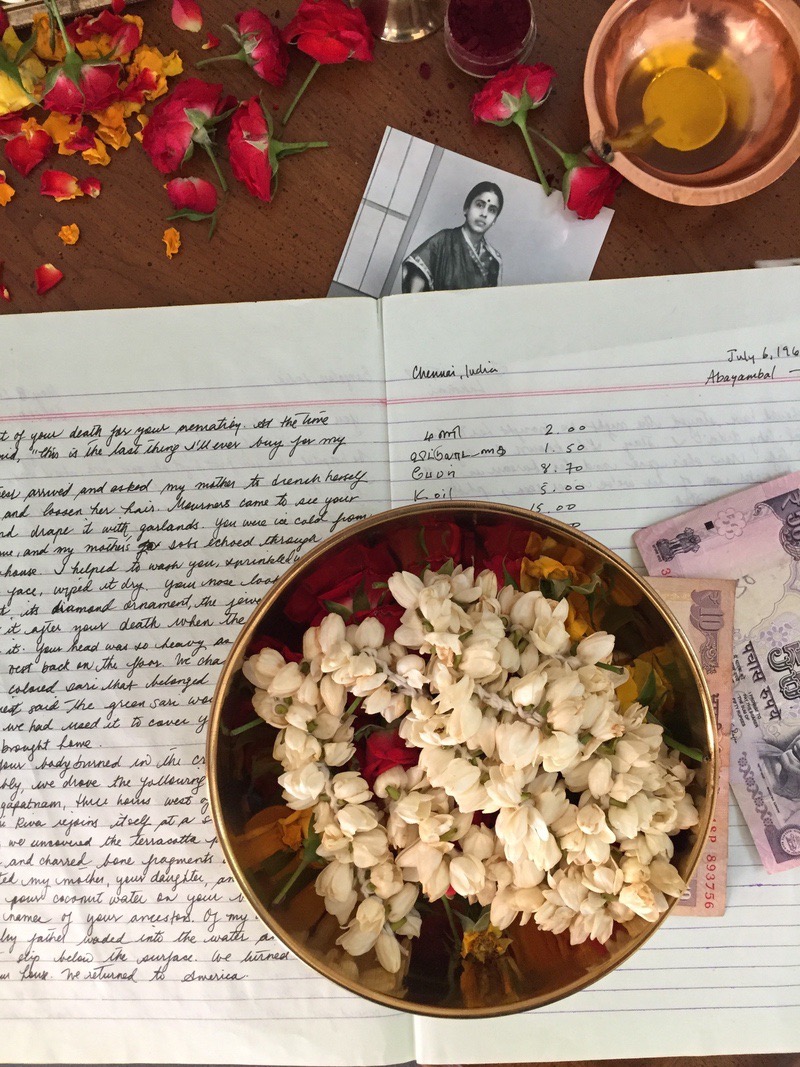

Lakshmi Ramgopal: Maalai 2017, my first sound installation was a very direct outgrowth of my grandmother’s death. She was someone who I felt very close to, so making the work came from the need to honour her legacy. Creating work for this installation also helped make sense of the loss I had experienced. Something I always remember her doing was praying all the time for everybody but herself. I wanted to recreate the Hindu rituals that I was familiar with but with a version where women decided the course of the ritual instead of the pujari or priest. The altar I created was one that I grew up with in my home and my grandmother’s home. However, in my recreation, I put images of women in my family including women who are alive which is very taboo. I also included conversations in Tamil between my grandmother, my mother and me from many years ago that were played on speakers as part of the installation. Another component of this piece was diary entries that I fabricated based on letters exchanged between my grandmother and great grandmother. These letters were a way for these women to sustain themselves and keep their relationships intact in spite of the emigration that separated them.

I want to add that religion is not a part of my practice in a superficial way, I guess what I am trying to say is that it was the way it was in my upbringings. It’s just there, present. Hinduism has always felt like a house without a room for me. I find that I process these rituals and traditions by recreating it in my work. Shortly after the passing of my grandmother, my brother had a daughter. The birth of my niece was really transformative for me just as much as the death of my grandmother. That also compounded my changing experience of religion because of all the different rituals we do for pregnant women, the naming ceremony and all of those things were vivid experiences for me. I had a special role in some of them as the sister of the father which was really meaningful to me. These events made me rethink my own childhood and what it means to actively choose not to be a mother. I think my art practise has been a way to play and experiment with the different selves that I have inside me.

With A Half-Light Chorus, 2018 there were some elements of religion like the references to flowers like jasmine and lotus which have a lot of significance religious and otherwise. It was also informed by medieval Sanskrit poetry that I had been reading at that time. Before my grandmother passed, I didn’t really make work that reflected me in terms of my personal history and family history. After she passed there was a very sharp pivot to just the work I am doing now. I think it’s made me a better and stronger artist which could have only come about with age and some passage of time.

Design Pataki: In addition to being an artist you are also a historian of the Roman Empire and currently teach Roman history at Columbia University. How do you make time to work on your art while also teaching?

Lakshmi Ramgopal: I have two careers and only one of them pays my bills. So that does dictate how I spend a lot of my time. When I was in graduate school, I had a lot of flexibility and autonomy in terms of my time and the work I do. As a professor, I’ve had to become a lot more vigilant about the kinds of commitment I take on. Especially because it’s very draining to take on both my academic work and artistic. It’s really hard and in many ways draining to put on performances which are really large and ambitious.

One of the ways I strike a balance is that I only take on projects that really speak to me, and offer me resources to do more than or different from what I have done in the past and help me to really to grow. I also now have an ensemble and really insist on them being paid and I don’t expect to work with them for free. And if I have to then I will pay them out of pocket. So in some ways being an academic has enabled me to be an artist because I am able to be the kind of artist and creative director that I want to be. I would be lying if it said it didn’t affect my health and sanity when I transition from working on a book during the day to transitioning or even teaching to rehearsal in the evening. I think the takeaway for me over and over again is to maintain a balance and make well-being a priority for me.

Design Pataki: What are some things you are currently working on?

Lakshmi Ramgopal: My art practice has been and will for some time be focused on Some Viscera, which is a body of sound and movement work that I have shared through site-specific ensemble performances over the last few years, including the performances associated with my installation A Half-Light Chorus and last year’s performances at Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art, and other locations (including an ice-cold stream in rural Wisconsin early in the morning). I think of the project as audiovisual, and I’m hoping to be able to do it next summer.

In addition, I’m writing my first academic book, tentatively titled Romans Abroad: Associations of Roman Citizens from the Second Century BCE to the Third Century CE. The book derives from my PhD thesis and explores how relationships between Roman and non-Roman trade groups in the Roman Empire shaped Roman imperial activity throughout and beyond the Mediterranean basin.

Design Pataki: In a piece for the Chicago Reader, a few years ago, you talked about what it means to be creating as an Indian woman. What has that learning process been like for you?

Lakshmi Ramgopal: The march toward 40 has been marked by a great deal more loss and pain than I experienced in my 20s, and I’m thinking as much if not more about my legacy. I’ve lived most of my life as I’ve wished, and this has been possible through extraordinary privilege and also enormous sacrifice in my personal life. I won’t have children, I think, so I want my nieces, Shakthi and Ishvari, to access as much of my own personal history as they want and to see their important place in it. What I make is indelibly impacted by them. I dedicated my installation A Half-Light Chorus to Shakthi, and the songs on my forthcoming record Some Viscera are a collection of lullabies I’ve written for both girls (as well as for my late grandmother). They, too, will likely spend time in their lives learning traditional Indian art forms, and they, too, can create with that knowledge anything they wish.