The Role Of Thoughtful Design With Abha Narain Lambah In Collaboration With IDF

Architecture is an amalgamation of the poetic aspirations of a space, and the social and environmental context to the science of building it. It is a materialized response to our cultural ambitions. The structures built as a response to these notions become a memorable part of our heritage over the years. These buildings and cities form a part of our collective memory in the way we engage with them. In an era where things are produced in an instant, it is the design of our building and cities through which our cultural memory takes form.

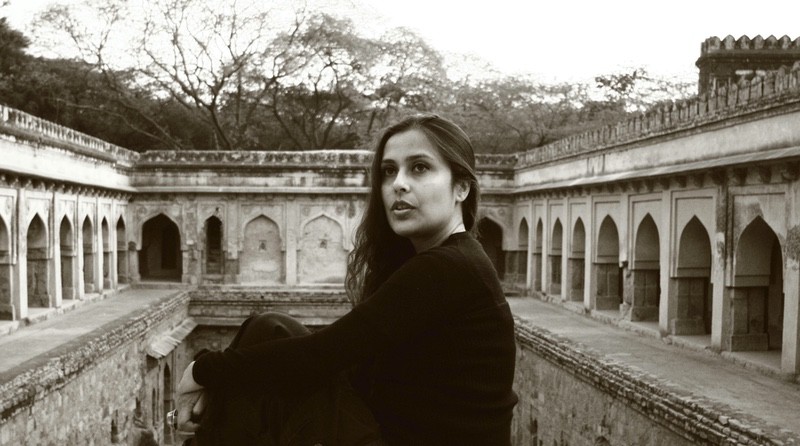

Abha Narain Lambah is a conservation architect based in Mumbai who has won 9 UNESCO Asia Pacific Awards for conservation, and has a leading architectural firm specializing in restoration conservation, museum design, historic interiors, and urban conservation management plans. Over the past two decades, Abha’s studio has worked on a diverse range of projects across India including the restorations of iconic structures in Mumbai like The Royal Opera House, Raj Bhavan, and Keneseth Eliyahoo Synagogue to name a few.

Abha’s work has consistently shown an intrinsic critical sensitivity towards the heritage of Indian cities, and her work grows increasingly more important in an age wherein Indian cities stand to lose their unique urban identities in quests for rapid modernization. She emotes strongly about the need for buildings to respect and respond sustainably towards their local urban context. Her keen eye towards analyzing and restoring distinctive spatial details is visible in the wide range of projects that her studio has conserved. This noteworthy attention to detail is what establishes her as a leading conservation architect in India.

In a special collaboration with India Design Forum – Building Debates, curated by Rajshree Pathy and Mrinalini Ghadiok, we speak with Abha for a glimpse into her personal narrative, and thoughts on matters concerning the design of our built environment. The IDF debate sessions have been specially curated to have an inclusive conversation about design of the built environment in our country. “The idea germinated from many conversations over the months where we found ourselves repeatedly questioning; what builds the blocks of architecture. So we thought – let’s fearlessly question the mechanisms that make Architecture relevant today,” say Rajshree Pathy and Mrinalini Ghadiok.

Abha Narain Lambah along with Ayaz Basrai and Asim Waqif led the conversation on building responsibly, and fearlessly questioned the mechanisms that make Architecture relevant.

Design Pataki: What are your thoughts on architecture creating a heritage for our future past, and the current attitude towards building?

Abha Narain Lambah: What we need to comprehend is that we are not just paid architects on hire, rather we have a responsibility towards the whole urban scape of the future. We also need to understand architecture as a profession, as a craft, is something which is beyond the defined design brief. It has the most distinctive impact on our cityscape. It is not about following trends and fashions to produce our buildings. Unlike any other product, architecture is really meant to last for a much longer time. The material, the durability of the structure, the quality of space largely impacts the imageability of the city and quality of life for its residents. And therefore, I think we need to take ourselves a little more seriously.

Design Pataki: What role do you think architects play in shaping up our cities?

Abha Narain Lambah: I think maybe we have a huge say. The reason clients come to us is that they know we have in-depth knowledge, and they trust us. We can either stick to the usual brief or think outside the box to come up with ideas that produce far deeper cultural value.

When I walked into the India Habitat Center, I saw how even architects can challenge the brief. Because India Habitat Center originally was going to be six different building projects and the architect was able to convince the clients that it should be done together as one urban institutional complex. The resulting project thus was an amazing amalgamation of various building programs along with a very strong architectural language. And the architect did engage with the client beyond his scope to inform the design. One architect was able to have a positive say on a huge urban chunk in Delhi.

Design Pataki: According to you, how can the design fraternity promote the discussion of thoughtful design and create a sense of pride for our buildings and cities with the public at large?

Abha Narain Lambah: Well, you know I think generally one can either talk or we can do. However very often we have to do both for whichever method works out there. There needs to be a gradual shift in thinking about the role architects can play in shaping up our cities. It is beyond just a typical building, rather it is also about what is the urban concept. The reason that it is crucial to convey this is that most of us when we are building in our cities, we are building on a rich diverse texture of urbanity. Cities like Bangalore, Chennai and Delhi for example have a certain character and what we usually tend to add, is an anonymous building. We must be more assertive in terms of what is the local material, the local stone used, what is the texture of the built form, etc. And even if we do it in a completely contemporary way somewhere it needs to respond to the surrounding urban context. When our buildings will respond to the local urban narrative, they will become a part of the city’s memory.

Design Pataki: Also, the general perception is that art, architecture, and conservation are very elite fields. How would you address this perception so that there is a more inclusive and open discussion towards thoughtful design of our built environment?

Abha Narain Lambah: If it is considered elitist it is partly because of us. It is a choice, if you do not engage with people nothing will come out of even the best of projects. It does not matter whether you are in politics or architecture. And I think both in politics and architecture you must go out and start working at the grassroot level, understand the reality of the place.

I personally feel like you can either consider your work as a job or as a responsibility. It is how you take it. You must do it conscientiously despite obstacles that come along the way. You can either play safe or you can engage and contribute towards a value driven design.

Design Pataki: How has the term ‘building responsibly‘ evolved for you over the years? Also, could you give a few examples from your experience as a professional?

Abha Narain Lambah: Yes. The first one is when I was a young architect and wanted to work with Joseph Allen Stein. Stein as an architect has built very contemporary buildings in historic areas. As a young architect it influenced me the most – because here was the American architect who was so respectful towards the Indian cultural context even though he was building with a contemporary aesthetic. He did so by mapping the historic contextual setting – the materiality, the colors, and textures. He beautifully responded to the Lodhi garden. There was no replicating characterization- he did not build domes but rather very contemporary modern structures which responded to the surrounding urban aesthetic. So, I believe architects should always have this in their nature to be culturally and socially responsive to the local context.

And personally, according to my own experience in 2007 – for Crawford market, Mumbai. This Victorian market in the city’s historic fort precinct was a Grade 1 heritage market structure and is a memorable part of the city’s memory. I persevered for more than seven years to ensure that it is conserved along with a holistic upgradation of the civic plaza and wholesale market. So, if I just said, “Oh my client wants something else,” that would be the easiest thing to do.

Design Pataki: You’ve said in an interview before referring to the Fountainhead – “Why should Howard Roark be a male figure? Why can’t Howard Roark be a woman?” Can you elaborate?

Abha Narain Lambah: When I was studying at the School of Planning and Architecture the ratio of girls to boys was 1 girl to 10 boys and today, I think it is the opposite. I just want to say that there are good architects and there are bad architects but there are not women architects and male architects. We study under the same college as our male colleagues dealing with sand, stone, brick and mortar – that is not treating me differently. If you are confident in your craft and your design, nobody can intimidate you.

Whenever we think of a great architect, we many times tend to classify that as a man. I do not think that being a good architect has anything to do with gender. Rather it has to do with how brave you are as a designer, how committed you are to your craft. Sometimes it is just sheer perseverance. I would say Howard Roark is a human who believes in what he is doing and has stuck to it. And that he did not compromise. He was true to his design aesthetic and his craft. So, if I just replace the name Howard with any other name …. a female name too – I think it stays the same.